Tom Purcell is a Pittsburgh Tribune-Review humor columnist and is Nationally syndicated exclusively by Cagle Cartoons, Inc.

While organizing my home office a few weeks ago, I came across a letter my grandfather wrote back in 1924.

While organizing my home office a few weeks ago, I came across a letter my grandfather wrote back in 1924.

He wrote that eloquent letter to his best friend’s wife, consoling her on the loss of her mother. His cursive handwriting was artful–perfect penmanship.

He wrote the letter when he was 21. Since he died at 34, when my father was only three, it is among the most cherished items I have from a grandfather I never got to meet.

Such is the power of the handwritten letter, an art that has died along with the art of cursive handwriting.

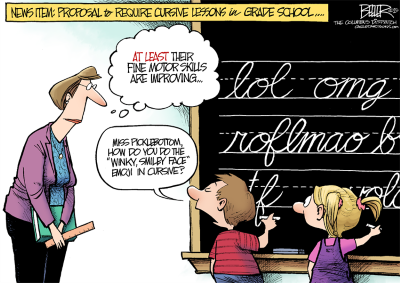

You see, many American schools have phased out lessons in cursive. There is a waning need for it in the modern era, some argue, and the classes take too much time.

Cursive originated centuries ago. It’s the result of technological innovations such as inkwells and quill pens made from goose feathers.

Because ink dripped when the quill was lifted from the paper, it made sense to connect letters in words together in one flowing line–and the art of cursive writing began.

Cursive became less necessary with the invention of the ballpoint pen, which does not leak and, technically, does not require cursive writing.

Changing technology, which led to electronic documents completed on computers, has also contributed to less need for handwritten signatures.

As a result, millions of younger Americans have not been taught cursive penmanship. But that’s being rethought, by no small number of educators.

Fourteen states have passed laws mandating that students become proficient in cursive writing.

Proponents of cursive argue that it must be taught for several practical reasons.

How can someone who can’t read cursive read and appreciate a handwritten note from Grandma, or original, historic documents such as the U. S. Constitution?

Proponents also argue that students who take notes using longhand, rather than a keyboard, are more likely to master subjects.

In Psychology Today, William Klemm, Ph.D., a Senior Professor of Neuroscience at Texas A & M University, argues that cursive writing “helps train the brain to integrate visual and tactile information, and fine motor dexterity….To write legible cursive, fine motor control is needed over the fingers. You have to pay attention and think about what and how you are doing it. You have to practice. Brain imaging studies show that cursive activates areas of the brain that do not participate in keyboarding.”

There are other important reasons to carry on the art of cursive handwriting and the art of the handwritten letter.

When was the last time you received a handwritten letter? The last time you wrote one?

Is there anything more wonderful than opening your mailbox to find an envelope with your name and address, and a friend or family member’s name and return address, handwritten on it?

I hate to admit it, but the last time I received such a letter was years ago, when my sisters and I sent our newly-retired parents on a trip to Florida. Each day that week, our mother wrote a letter and mailed it to one of us.

She and my father both have impeccable penmanship. Her letters look more like art than a form of communication. My sisters and I spent hours sharing those letters and laughing out loud.

We still have those letters, and they still make us laugh out loud.

That’s the power of a letter handwritten in cursive.