Editor’s note: Gary Farral posted this information on Facebook, on Thursday, August 24, 2018. The author is Vin Suprynowicz, an American Libertarian author who formerly edited editorial pages for the Las Vegas Review-Journal.

On November 15, 2003, an 85-year-old retired Marine Corps Colonel died of congestive heart failure, at his home in La Quinta, CA, southeast of Palm Springs. He was a combat veteran of World War II. Reason enough to honor him. But this Marine was a little different. This Marine was Mitchell Paige.

On November 15, 2003, an 85-year-old retired Marine Corps Colonel died of congestive heart failure, at his home in La Quinta, CA, southeast of Palm Springs. He was a combat veteran of World War II. Reason enough to honor him. But this Marine was a little different. This Marine was Mitchell Paige.

It’s hard today to envision or, for the dwindling few, to remember what the world looked like on 26 October 1942. The U. S. Navy was not the most powerful fighting force in the Pacific; not by a long shot. So, the Navy basically dumped a few thousand Marines on the beach at Guadalcanal [Island.]

Platoon Sgt. Mitchell Paige and his 33 riflemen set about carefully placing their four, water-cooled, .30-caliber Browning machine guns, manning their section of the thin khaki line, which was expected to defend Henderson Field against the assault of the night of 25 October 1942. It’s unlikely anyone thought they were about to provide the definitive answer to that most desperate of questions: “How many able-bodied U. S. Marines does it take to hold a hill, against over 2000 desperate and motivated Japanese attackers?”

Nor did the commanders of the Japanese Army, who had swept everything before them for decades, expect their advance to be halted on some jungle ridge, manned by one thin line of Marines in October of 1942.

But by the time the night was over, The Japanese 29th Infantry Regiment had lost 553, killed or missing, and 479 wounded among its 2554 men, historian David Lippman reports. The Japanese 16th Regiment’s losses are uncounted, but the [U. S.] 164th’s burial parties handled 975 Japanese bodies….The American estimate of 2200 Japanese dead is probably too low.

Among the 90 American dead and seriously wounded that night were all the men in Mitchell Paige’s platoon–every one. As the night of endless attacks wore on, Paige moved up and down his line, pulling his dead and wounded comrades back into their foxholes and firing a few bursts from each of the four Brownings in turn, convincing the Japanese forces down the hill that the positions were still manned.

The citation for Paige’s Medal of Honor Citation defines the event: “When the enemy broke through the line directly in front of his position, P/Sgt. Paige, commanding a machine gun section with fearless determination, continued to direct the fire of his gunners until all his men were either killed or wounded. Alone, against the deadly hail of Japanese shells, he fought with his gun, and when it was destroyed, took over another, moving from gun to gun, never ceasing his withering fire.”

In the end, Sgt. Paige picked up the last of the 40-pound, belt-fed Brownings (the same design which John M. Browning fired for a continuous 25 minutes until it ran out of ammunition, glowing cherry red, at its first U. S. Army demonstration) and did something for which the weapon was never designed. Sgt Paige walked down the hill toward the place where he could hear the last Japanese survivors rallying to move around his flank, the belt-fed gun cradled under his arm, firing as he went.

The weapon did not fail.

At dawn, Battalion Executive Officer Major Odell M. Conoley was first to discover the answer to our question, “How many able-bodied Marines does it take to hold a hill against two regiments of motivated, combat-hardened, Japanese infantrymen, who have never known defeat?”

On a hill where the bodies were piled like cordwood, Mitchell Paige alone sat upright behind his 30-caliber Browning, waiting to see what the dawn would bring.

One hill; one Marine.

But, “In the early morning light, the enemy could be seen a few yards off, and vapor from the barrels of their machine guns was clearly visible,” reports historian Lippman. “It was decided to try to rush the position.”

For the task, Major Conoley gathered together “three enlisted communication personnel, several riflemen, a few company runners who were at the point, together with a cook and a few messmen who had brought food to the position the evening before.”

Joined by Paige, this ad hoc force of 17 Marines counterattacked at 5:40 a.m., discovering that this extremely short range allowed the optimum use of grenades. They cleared the ridge.

And that’s where the previously unstoppable wave of Japanese conquests finally broke and began to recede. On an unnamed jungle ridge, on an insignificant island no one had ever heard of, called Guadalcanal.

But who remembers, today, how close-run a thing it was, the ridge held by a single Marine, in the autumn of 1942?

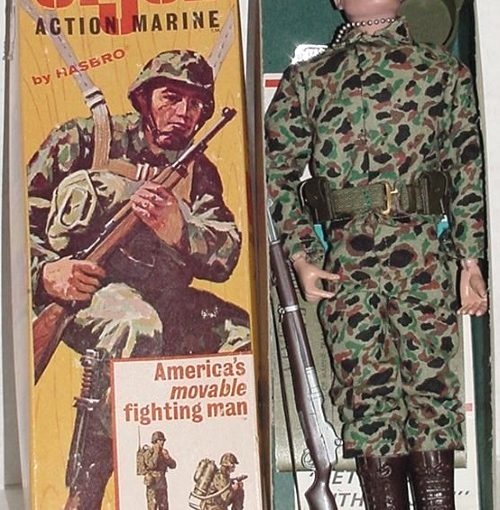

Sometime after, when the Hasbro Toy Company telephoned, asking permission to put the retired Colonel’s face on some kid’s doll, Mitchell Paige thought they must be joking.

But they weren’t. Today, that’s his face on the little Marine they call “G. I. Joe.”